Is the Web about to get fun again?

Early in my career, I built a reputation for being “the social guy.” (True story: I was the first person to launch a social presence for a global brand.) I helped companies manage social accounts before algorithms, influencers, and bots.

This was the “good old days” when social media was like the Wild West. And it was fun!

Then came algorithms, and the big platforms quickly learned that nothing engages people (and sells ads) like rage and anger. Today, social media is starting to feel like an obligatory grind instead of a fun way to engage with your audience.

But that might be about to change.

A few days ago, something went very awry with Threads moderation and content policy. How bad? Journalists-getting-locked-out-of-their-accounts bad, which brings us back to the age-old question of content moderation and why it’s so opaque on yet another Meta-owned and operated platform.

Initially, I was a huge proponent of Threads and became a de facto advocate for it, arguing that you’d be missing the bigger picture if you just wanted Threads to be Twitter 2.0. But after suffering months of opacity, I’m starting to lose my patience. I know I’m hardly alone.

Relevant to this discussion about moderation, a new report gives us insights into what most of us in the space have known for years. Misinfo and hate spreaders make up a tiny, tiny percentage of overall social media users, and yet they’re the ones who cause the most harm.

ScienceDirect Report: A Small Group of Bad Actors Are Responsible for Toxicity on Social Media

A recent report from ScienceDirect studied and analyzed the social media accounts that create and normalize toxic views, making those views appear more widespread than they actually are.

Inside the Funhouse Mirror Factory: How Social Media Distorts Perceptions of Norms validates what many of us who use social platforms professionally have observed for years: Fake news, misinformation (election, health, COVID, etc.), and “discontent” are spread by a fraction of a percentage of the overall social media audience.

This passage (from the report, with footnotes) drives it all home.

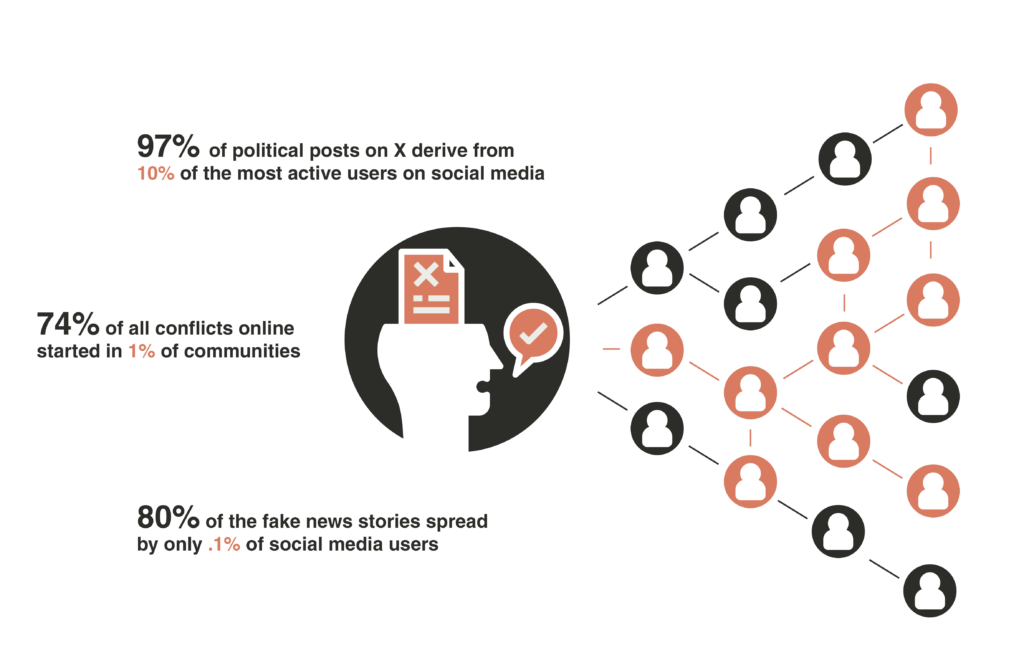

“74 % of all online conflicts are started in just 1 % of communities[5], and 0.1 % of users shared 80 % of fake news.”

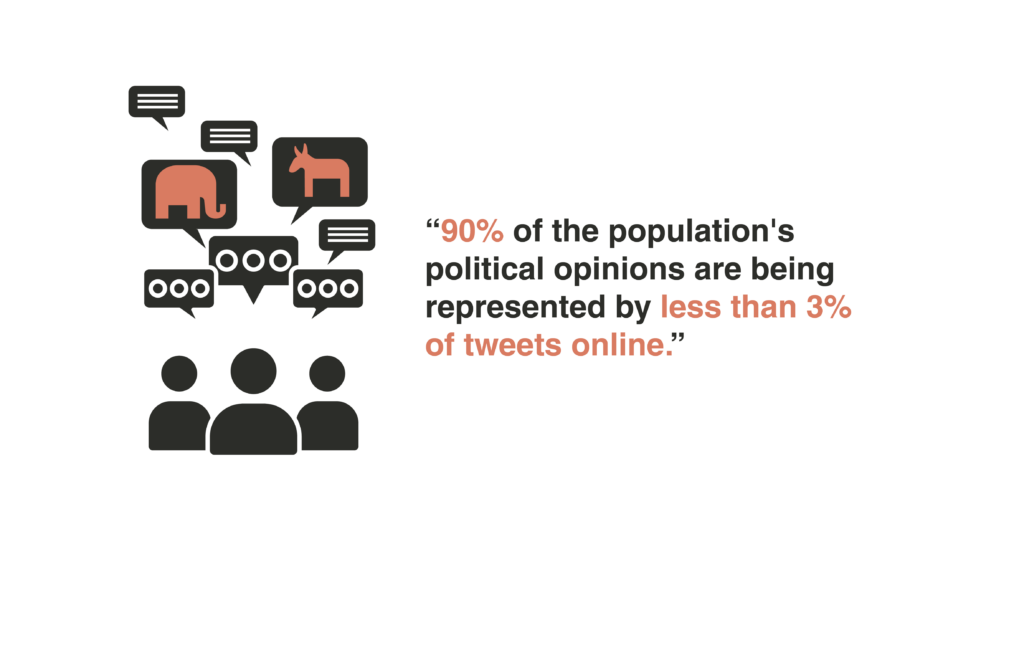

The paper presents a compelling argument with data to back it up: Once false perceptions take hold in online groups, those perceptions quickly become normalized. Small groups of bad actors wear us all down, normalizing toxic or separatist viewpoints, eventually making those views seem widely held, when in fact those ideas represent the opinions of a minority cohort.

Put simply, we’re not as polarized as online communities make it appear.

“Not only does this extreme minority stir discontent, spread misinformation, and spark outrage online, they also bias the meta-perceptions of most users who passively “lurk” online. This can lead to false polarization and pluralistic ignorance, which are linked to a number of problems including drug and alcohol use [8], intergroup hostility [9,10], and support for authoritarian regimes [11].”

This normalization isn’t just bad for our political discourse and our future as a pluralistic democracy (all serious enough!) but also our collective health outcomes. Example from the report: If it appears to young people that over consumption of alcohol is “normal” and widespread (when it isn’t), that misconception poses a public health danger (and could lead to shorter overall lifespans amongst those young people).

Let’s go back to what I think is the most critical stat: Fake news stories are spread by 0.1% of online users. That means the rest of us (99.99 percent of us!) are either passively reading information (and probably trying to find the good stuff) or doing things that are neutral where online discourse is concerned.

The report includes high-quality research (in stark contrast to the non-science behind the current social media panic) and should motivate platforms to invest in large-scale moderation methodologies to keep 1/100th of all bad info off of their platforms to protect the rest of us.

So, RE: Threads/Meta and its broken moderation systems.

- Why is Threads punishing the rest of us when only a fraction of a fraction of its users are the problem?

- Why doesn’t Meta use its considerable resources to exile these tiny pockets of bad actors? (Answer: Rage is good for business.)

- Why isn’t Meta more transparent about its current moderation methods?

- Why can’t Threads let the rest of us flourish on its three platforms, and give us clear rules of the road when it comes to news and politics?

Meanwhile, we now have alternatives. Like many people, I have started experimenting with Bluesky again.

How Many People Are Really Flocking to Bluesky?

Recently on Threads/Instagram suddenly and seemingly without warning, big accounts that posted political content started getting either throttled or deprioritized by the algorithm. (I’m not talking about fringe players, either. I mean people like highly respected tech journalism icon Walt Mossberg.)

The furor got big enough that not one but two respectable tech publications wrote not one but two respectable stories about it.

First, in The Verge, “Instagram and Threads moderation is out of control”.

“Moderation is a perennial problem on social media, but based on social media posts and The Verge staff’s own experiences, Meta is currently banning and restricting users on a hair trigger. One of my colleagues was locked out of her account briefly this week after joking that she “wanted to die” because of a heatwave.

Others, like Jorge Caballero, say the automated system has added fact checks with mistakes to material it detects as political, as well as throttling posts with factual information for events like hurricanes. Some have dubbed their situation “crackergate,” as recent posts mentioning saltines or the words “cracker jacks” have been instantly removed.”

The second story in TechCrunch, Bluesky joins Threads to court users frustrated by Meta’s moderation issues, is a micro study in how the social web is really starting to fracture (in a good way). Bluesky (David) took advantage of a moment and seized on the opportunity to steal users from Threads/Meta (Goliath).

“The company then clarified several key ways Bluesky is different from Threads in terms of moderation. Similar to other social networks, it does employ a moderation team that follows a set of community guidelines. However, Bluesky notes that its team won’t de-rank content if it’s about politics — something that Meta actively chose to avoid ahead of the contentious U.S. election season.”

(Also worth noting, when X owner Elon Musk updated Twitter’s common-sense blocking feature into a total kludge, Bluesky started adding over 500k users a day, making it the fifth most downloaded free app. Ask anyone who makes a free app if that’s a good day or not; it’s gangbuster.)

The issues that plagued Threads wonky moderation tweaks included locking out journalist (who authored the linked story in the Verge) Umar Shakir from his Instagram account.

Either Threads wants to be a home for serious people, or it doesn’t. It’s really that simple.

If Threads is going to stop the bleed, whether it’s perceived or not, Meta’s leadership needs to be clear about how they’re addressing large-scale moderation issues. Threads has yet to clarify how it defines “political” content. Its leadership continues to state that politics “will be limited” on the platform, but refuses to say what that even means.

So Bluesky (see my mini review of the app not long after I joined in 2023) is pouncing. Is it a great app? It’s…fine. But it’s improving quickly and showing us a way that we can have competing networks with different feature sets.

But maybe, just maybe, the “break up” of social media we’re seeing now bodes well for the future.

The Social Web is Fracturing. And that’s a good thing.

Unless you live under a rock, you’ve probably read or understand at least a few things about the so-called Fediverse, or the decentralization of social platforms. In the wake of Twitter, perhaps you’ve been baffled by a few Mastodon servers or even tried to start your own.

Right now, a handful of open standards are competing for viability so more of us can have “portable” social handles that can be republished on various feeds throughout the internet. If you’re thinking of the social media equivalents of WordPress and email, you’re not far off. Threads, for example, allows Fediverse sharing via ActivityPub.

Today, it’s not going to change your behavior a whole lot. But if your feeds are anything like mine, there are a lot of very smart, compelling conversations happening about what this decentralization movement means for the rest of us.

I can’t say it any better than former Stanford Internet Observatory research manager for and someone who knows a thing or two about disinformation, Renee DiResta:

“Since the Bluesky vs Threads debate is all over my field: we’re in the early stages of the Great Decentralization. There will not be one winning “public square” – and that’s great bc there was never one offline either. People will choose the environments they want to be in, and post differently on different platforms.”

It’s hard to make a better argument for the aspirational aspects of DiResta’s position here than what happened on Threads last week. Also, there are plenty of us who are old enough to remember a time when this described the web in the pre-social media era.

When those apps—especially Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—were new, the heady impact of network effects at scale was nothing shy of thrilling. Everyone could suddenly talk to, well, everyone. I’m sympathetic about how the sudden rush of quite literally billions of people (in the case of Facebook and YouTube) was equal parts exciting and headache-inducing for the founders. (My sympathy ran out at the exact moment when all of those people became billionaires.)

In reality, not everything you say, do, or publish needs to be seen by a worldwide audience simultaneously. In fact, specialization and audience “buckets” can be good things. Most of our clients at Fullerton Strategies don’t sell products to everyone on Earth.

What clients do want is a way to reach actual customers, even if it means companies like mine revert to the “good old days” when we had to know the specific places those demos were gathering.

Global reach will still be achievable, especially when you work with the right people who know where your personas are hanging out. (It’s called “marketing,” and it’s still very much a thing.) Facebook made it very easy and affordable to target audiences with very cheap ads. The future of advertising will likely look a whole lot more like the past.

The Future Belongs to Those of Us Who Embrace an Uncertain Future for Social Networks

No one knows exactly where this is all headed. And that’s a good thing. I think we’re all about to collaborate in smaller, more niche communities where we have greater moderation tools at our disposal. Most people want to have fun and resent the sliver of a fraction of bad-faith users who know exactly how powerful divisiveness can be, even when that divisiveness only exists on a smartphone.

If the future of social media looks more like discrete groups of a few hundred thousand people with shared interests, solid moderators, and well-documented moderation policies, I’m going to be a pretty big cheerleader for that future. Just like we self-assign physical spaces, it’s perfectly okay for you to find an online tribe. Wanting to feel safe and informed doesn’t make you a snowflake. It makes you a reasonable, smart human being.

Adam Mosseri is a lot of things, but he’s no idiot, which is probably why he issued this apology. Threads is still a better and healthier place for discourse than X, which has devolved into the absolute chaos of a pure misinformation farm. If I were running a social platform, I wouldn’t entertain the comparison. But we are where we are.

It took the better part of two decades to get here, and it’s time for a change. It can’t come soon enough and I’m so excited to be a part of it.